I discovered Bob Books in the 1990s when my sister was learning how to read, and became an instant fan.

Create a simple book around a few well-chosen sounds to give children early experience reading on their own. Build confidence. Add another book with some different sounds but stick to the soft vowels. Add a new book that integrates a wider variety of sounds. In short order, a child is reading before setting foot into kindergarten.

When it was time for my niece to read, I made up some of my own phonics-controlled stories for her, though mine tended to be goofier and to have drawings and culminating scenes that wouldn’t get a thumbs-up from Scholastic: “THE FAT CAT SAT ON SAM’S BAD DAD. SAM WAS GLAD.” I remember Sam’s closing smile as having a lopsided jack-o’-lantern quality with which I was pleased.

This didn’t feel like homework for me or for my niece. It felt like fun. Controlling for sounds, though, made the fun possible.

I don’t want to wade too deeply into the reading wars because my feelings about the decades of nonsense inflicted on American educators and grade-schoolers by the unforgivable nitwits at Morningside Heights Polytechnic don’t qualify for polite conversation, but I will say that focusing on teaching very young children to sound out words is the way to go, especially for children who most need help. Even in book-filled houses with lots of verbal interaction, time spent sounding out C-A-T is time well spent.

“Learning how to read” means a number of different things, though, and to really learn how to read once you gain enough momentum to keep from falling backward, the best thing to do is to lean slightly forward, keep those stubby little legs moving, and stop worrying about difficult words and sentences. Being a small child means that even if you crash into the wall or fall onto your face, the numbers for mass, acceleration, and altitude are on your side. You should be fine.

So read fast. Read difficult. Untether yourself from the child harness of the grade-level progression of state-mandated curricula and the kid’s section at the bookstore. Onward! Ad victoriam!

The children I’m addressing—unless I’m seriously misunderstanding my subscriber base—are of course hypothetical children I had to dream up to follow up on a metaphor. I do, though, wish that writers, publishers, teachers, and parents would encourage non-hypothetical children into a headlong rush into reading rather than a tranquil glide.

As a weird kid who read too many hard words and sentences too early and grew up to be immensely grateful for it, I would urge children’s authors not to try too hard to be age-appropriate. Like millions of other weird kids, I benefited from having access to books written when people worried less about terrorizing the young with polysyllabic words, rhetorical figures, semicolons, and long subordinate clauses. I grew up with books I could return to decade after decade as a different kind of reader, books that I could hear in voices that were neither cartoonish nor condescending, books that gave me at least an inkling of the polyglot musicality, infinite recursiveness, and stupefying magnitude of human language.

People have noticed the lexical challenges in Beatrix Potter for a long time. The books are obviously for young children, but the little humans had best be buckled up for “alacrity,” “lamentable,” and “soporific” if they want to read along with the bunny pictures.

I like that some of Potter’s most characteristic vocabulary moments come when she is annoyed and wants us to be as well. In The Tale of Mr. Tod, she is especially provoked by Tommy Brock the badger, who has stolen Mr. Bouncer Bunny’s grandchildren and has plans to eat them. Potter’s rage, though, is euphemized into achievement-test prep words and middle-class concerns:

The sight that met Mr. Tod's eyes in Mr. Tod's kitchen made Mr. Tod furious. There was Mr. Tod's chair, and Mr. Tod's pie dish, and his knife and fork and mustard and salt cellar and his table-cloth that he had left folded up in the dresser—all set out for supper (or breakfast)—without doubt for that odious Tommy Brock.

When he came back after removing the coal-scuttle, Tommy Brock was lying a little more sideways; but he seemed even sounder asleep. He was an incurably indolent person; he was not in the least afraid of Mr. Tod; he was simply too lazy and comfortable to move.

The semi-fancy words trace back to French and further back to Latin, but Potter’s language is also well grounded in the soil of the Britons. “Brock” is a dialect term for “badger” in Northern England. “Brock” is also Scots for “badger” as well as “dirty, malodorous person,” and “broch” is “badger” in Welsh, which traces back to the Proto-Celtic *brokkos. “Brock,” like “tor” and “bannocks” and “coomb,” is one of those rare Celtic-to-English connections that managed to survive the invasions of the Romans, the Saxons, and the Normans. All of this was of course utterly outside of my understanding given that I was a child reader in Alabama instead of Gwynedd or the Lake District, but when I learned about some of these things years later, I got to feel the thrill of clicking a puzzle piece into place.

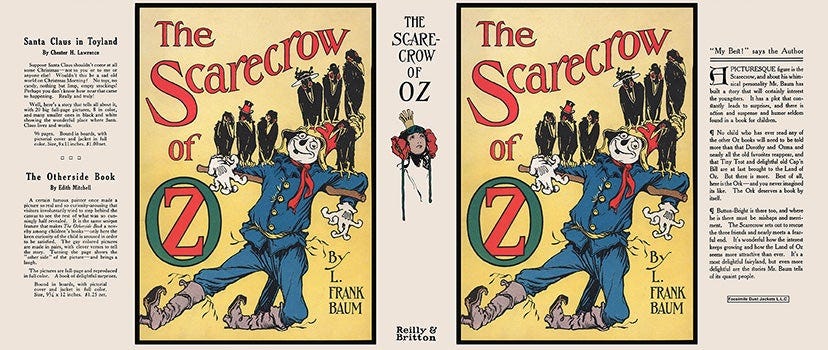

Even though The Wonderful Wizard of Oz attracts older readers than The Tale of Mr. Tod, L. Frank Baum’s language is closer to being controlled for difficulty than Beatrix Potter’s1. Pages can go by without anything resembling “alacrity” or “soporific” or “odious.” Even Baum, though, gives us “greensward,” “vexed,” “soldering,” “mar,” “thereupon,” “undergo,” “garret,” “brocaded,” “obliged,” “bewilderment,” “ventriloquist,” “counterpane,” “prim,” “wistfully,” “sulkily,” and “reproachful.” He is so attached to “bade” that he uses it eight different times.

When he gets to chapter 20, “The Dainty China Country,” he gets quite excited about a vista that no Oz illustrator I’m aware of has been able to live up to. (W. W. Denslow got things off to a terrible start.) The main way Baum communicates his enthusiasm for Dorothy and company’s first sight of China County is by casting aside any concerns he might have about age-appropriate sentence length:

There were milkmaids and shepherdesses, with brightly colored bodices and golden spots all over their gowns; and princesses with most gorgeous frocks of silver and gold and purple; and shepherds dressed in knee breeches with pink and yellow and blue stripes down them, and golden buckles on their shoes; and princes with jeweled crowns upon their heads, wearing ermine robes and satin doublets; and funny clowns in ruffled gowns, with round red spots upon their cheeks and tall, pointed caps.

The sentence can be distilled to an essence of “There were . . . all these things,” with the last thing being “funny clowns,” making it easier in practice than it looks to be at a distance, but at eighty words long, it nonetheless qualifies as a mouthful for an audience that includes members who still have some of their baby teeth.

Undaunted, the children of the early twentieth century read The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and drove the demand for its thirteen sequels over the next two decades. Baum’s sentences resemble his story-making style—a jovial mix of directness and “Maybe I’ll try this now?”—and despite the unevenness that results, the Oz books continue to sweep up readers just as they swept up Malala Yousafzai, Ray Bradbury, Salman Rushdie, Stephen Sondheim, and Martin Gardner. Strange as it might seem, Gore Vidal was also among those swept up, and surely one of Baum’s singular achievements is filling little Gore (or little Eugene) with a childlike sense of wonder.

Unlike Baum or Potter, L. M. Montgomery did not contribute to my childlike sense of wonder. Anne of Green Gables wasn’t something I rejected. I just never ran across it. Perusing it to write what you’re now reading, though, I understood from the first paragraph that my childhood reading life would have been even better if Montgomery had been part of it:

Mrs. Rachel Lynde lived just where the Avonlea main road dipped down into a little hollow, fringed with alders and ladies’ eardrops and traversed by a brook that had its source away back in the woods of the old Cuthbert place; it was reputed to be an intricate, headlong brook in its earlier course through those woods, with dark secrets of pool and cascade; but by the time it reached Lynde’s Hollow it was a quiet, well-conducted little stream, for not even a brook could run past Mrs. Rachel Lynde’s door without due regard for decency and decorum; it probably was conscious that Mrs. Rachel was sitting at her window, keeping a sharp eye on everything that passed, from brooks and children up, and that if she noticed anything odd or out of place she would never rest until she had ferreted out the whys and wherefores thereof.

Montgomery knows the names of things—of alders and ladies’ eardrops—and shares them. She trusts me, and apparently would have trusted my child self, to puzzle out “traversed” and “reputed.” She trusts me with the delightful strangeness of “dark secrets of pool and cascade” and with a stream that thinks and thinks of others and of their thoughts about the stream. She gives me a chance to notice, in whole or in passing, the alliteration and consonance and wordplay that bring the paragraph to a close. She is not writing for children. She is writing well.

I won’t go on and on about Anne of Green Gables because I am an initiate and haven’t yet done my due diligence by rereading it at least once. I will, though, recommend that you make it at least to chapter sixteen, when Anne interjects a 686-word speech into the dialogue without pausing to breathe, in the course of which she includes baking a cake, a casual “prob’ly” a la John Wayne, a story about death by smallpox, watering a grave with teardrops, pudding sauce, Protestantism, Catholicism, “cloistered seclusion,” a mouse that drowns in pudding sauce, pigs, and “mortification”—and gets so carried away in her own gusto that she doesn’t notice that her young friend Diana has inadvertently gotten drunk because Anne has inadvertently served her currant wine instead of raspberry cordial. The chapter concludes with Diana’s mother, Mrs. Barry, being mean to Anne, partly because Mrs. Barry is mean by nature and partly because Mrs. Barry is annoyed that Anne uses “big words” like “intoxicate.”

That last part has the feel of an author being autobiographical, and readers whose tastes are not aligned with Mrs. Barry’s should find much to like in Montgomery. And in Anne.

Robert Louis Stevenson was invited into my childhood about as pointedly as Montgomery was not. My dad must have been a fan at some point before moving on to Greene, Roth, le Carre, Michener, and Wouk, and multiple copies of Treasure Island and Kidnapped were scattered through the house. Disney’s 1950 Treasure Island made the rounds on television—live action, in Technicolor!—and the movie was a serviceable gangplank to the book even if Bobby Driscoll’s Jim Hawkins seemed too obviously a “gee whiz” kind of kid from Cedar Rapids, Iowa2. I also had an abridged audiobook that I listened to on a suitcase record player.

Partly because of this spoon-feeding—which I admit cuts against my thesis—I read Treasure Island more times than any other childhood book except for The Hobbit, Where the Sidewalk Ends, The Wind in the Willows, Kidnapped, and Bears in the Night. I plowed through the thing because I wanted more than I got from the abridgement and the movie, and this required looking things up in dictionaries and encyclopedias, guesswork, worrying my mom by asking about things like what a “mizzen-top” was, and not getting discouraged when there were things I didn’t understand.

Looking at these requirements now, I see valuable skills.

Stevenson’s sentences clip along nicely and feature plenty of what C. S. Lewis might call “good plain” words. Some of his vocabulary, though, is intimidating. Even if you leave out most of the martial and nautical terms, as I have in the list that follows, there remains a lot for a young reader to learn:

unweariedly, diabolical, admixture, derision, mutilated, calumnies, prodigious, emboldener, hummock (meaning a knoll or ridge), knoll, promontory, fawning, dingle (a small hollow), pannikin (a cup you might dip into a barrel filled with grog), canikin (another cup), spurned, durst, catechism, atrocious miscreant, skulking, condescending, undulating, hither, thither, incongruous, dirk, gallipot (a druggist’s earthenware pot, used metaphorically by Stevenson to refer to a small boat), dell, supplication, palisade, athwart, tip us a stave (meaning “give us a song”), duff (the pudding, not the beer), assizes, beetling (jutting), trebly, connoisseur, rheumatics, gaskin, dexterity, tallowy, coracle, slewed (turned on a fixed point serving as an axis, as with a telescope or gun on a swivel), dysentery, acquiescence, bandoleer, tremulous, stockade, disaffected, disquietude, sidled, leeward, scuppers under (the ship is rolling so that the draining outlets on the top-deck are dipping into the water), amphitheater, hamlet, alow and aloft (above and below), magistrate, derisively, carcasses, accoutrement (used to satirize Ben Gunn’s filthy rags and, presumably, everyone in France), abominable, gattling (which has no OED entry but seems onomatopoeic and perhaps means something like “indistinct chattering”), indomitable, extricate, sward

Some of these words I surely passed by without comprehending at all. Many, though—like “diabolical,” “derision,” “mutilated,” “calumnies,” “skulking,” “spurned,” “supplication,” “sidled,” “derisively,” “carcasses,” “accoutrement”—I got from context because Stevenson tends to make this easy. (There is no way to read Treasure Island without knowing what a “coracle” is.) Far from perplexing me with difficult words, Stevenson taught them to me. With words like “unweariedly,” “admixture,” “emboldener,” “acquiescence,” “tremulous,” “disaffected,” and “disquietude,” he taught me about affixes and the malleability of language before I knew precisely what affixes were or “malleability” meant. With “pannikin” and “canikin” and “bandoleer,” he taught me to pay attention to wordlets like “pan” and “can” and “band.” With “gattling,” he taught me how to deal with words that are too abstruse even for the Oxford English Dictionary but that can chatter with perfect fluency in story.

Of course children don’t read Treasure Island as often as they once did. Henry Fonda’s Norman Thayer character in On Golden Pond was grouchy about this forty-four years ago. Whatever objections one might have to Treasure Island, whether it’s solving problems with violence or failing the Bechdel test in a truly spectacular fashion, I think the world is worse off because school-aged children don’t read it anymore. Our post-literate society is especially post-literate when it comes to boys, and I am certain that women and men would both benefit if boys read more, even if they sometimes bored people by talking about—or alarmed people by asking about—musketry and mizzen-tops.

I’ll close with Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, which once upon a time might have been my favorite book but is also very peculiar3. Parts of it seem to be written for readers who want something like A. A. Milne. Parts read like the more mundane and cozy moments in The Chronicles of Narnia. Parts read like a Bertie Wooster beast fable but with more pratfalls—others like an H. Rider Haggard adventure set in Jerome K. Jerome’s littlest of Englands. Snippets of it recall the sadness that plagued Grahame’s life.

The “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn” chapter, which is the most peculiar chapter in the book, reads like an Edwardian pastoral shot through with mysticism. I skimmed through it fairly quickly as a young child because like most inexperienced or inept readers (and most inexperienced or inept people) I held the natural world in contempt without realizing it. As I got older, though, I processed it in an entirely different way, and the act of rereading it resembled the numinous discovery experienced by the characters in the story. I don’t know how old I was when I first read it this way but remember where I was sitting in my room and that it was sunny outside.

In this chapter that is probably nearest his heart, Grahame drops any pretense of limiting himself to the vocabulary of the nursery. A willow wren sings in “the dark selvedge of the river bank.” The edge of evening displaces “the sullen heats of the torrid afternoon.” A quarter of the horizon shows black “against a silvery climbing phosphorescence that grew and grew.” The Rat and Mole explore “the runnels and their little culverts.” Mole can’t hear the entrancing music the Rat does, only “the wind playing in the reeds and rushes and osiers.” The Rat’s “helpless soul” is “swung and dandled” by something he doesn’t quite understand. As the light rises, they can see the color “of the flowers that gemmed the water’s edge.”

Then they have an encounter that leaves them overcome with awe. This is quickly displaced by fear, then by sadness, briefly by despair, and at last by forgetfulness. Grahame’s diction gets noticeably simpler when the experience approaches the ineffable. Plain language steps forward when the tension reaches its height and also when it fades, but having to shift to ordinary words makes the blessed ordinariness of “the birds” and “the dawn” seem something other than ordinary.

Ordinary language touches the heart because we knew it first and because it binds us together. Tennyson, who could be a man of many words, some of them fancy, turns to the ordinary in his In Memoriam to show what it feels like to lose a person you love:

He is not here; but far away

The noise of life begins again,

And ghastly thro’ the drizzling rain

On the bald street breaks the blank day.Tennyson has good company in the plain language of misery. The first metaphor in the second quatrain of Wordsworth’s “She Dealt Among the Untrodden Ways” sticks in the mind because of its ordinariness, and the Lucy of the poem who has “ceased to be” will recur to readers again and again because she is “A violet by a mossy stone”—a perfect image of beauty in isolation, and in vulnerability, that asks so little of us in terms of language.

The power of plain language can also be seen in the abuse of language that isn’t. I’m not certain just how comical Poe meant for the many-tongued, sesquipedalian geniuses in his stories to be, but given his own description of his detective stories as “tales of ratiocination,” I think he wasn’t always in on the joke4. Something similar is frequently true of H. P. Lovecraft, as in sentences like this one from “The Horror at Red Hook”:

From this tangle of material and spiritual putrescence the blasphemies of an hundred dialects assail the sky.

With his use of “an” complementing “putrescence” and “assail,” Lovecraft manages to fancify even an indefinite article. This is funny in a plummy accent. It’s funny as Eliza Doolittle.

Fortunately, we don’t have to choose between eternal plainness and Lovecraft at his purplest. Sometimes fancy words like “recreant” or “superflux” can suit the circumstance perfectly, as they do for King Lear. Children’s authors who know the power of plain words but also choose from a large lexicon are givers of gifts. Beatrix Potter’s epithets relate to technical terms, many of which have Latin roots, in philosophy, law, and the sciences. Baum and Montgomery show how a flood of words can crystallize a complex scene or create a sense of excitement. Stevenson’s fine-grained storytelling hints at how much world there is to pay attention to. Kenneth Grahame suggests that words can communicate something about an experience even when words are beyond it.

Children should not start a regimen of SAT word lists before they learn how to tie their own shoes. If, however, they happen to come across “recreant” or “gattling” or “selvedge” too soon, they will survive. Their very experience of unreadiness will also prepare them for experiences later on: for technical language, for abstraction, for hyper-specification, for languages that aren’t their own, for book chapters that begin with “Ineluctable modality of the visible,” for a wider selection of beauties and sadnesses, and for communing with people who use words differently because they lived a long time ago. The richer their diet is in words in stories, as long as they’re still enjoying themselves, the better. I would let them help themselves to every last morsel they can eat.

Part of this is about Baum’s default mode of expression when writing fiction. A quick inspection of one of his pseudonymous novels for adults, The Fate of a Crown, as Schuyler Staunton, uncovered language more advanced than you find in Oz, but difficult sentences are still few and far between. I reviewed the thing at breakneck speed and can’t say I was tempted to slow down much, but I will say—if you don’t mind plot spoilers!—that there is a heroine-rescues-hero moment, that the republican cause triumphs in Brazil, and that Lesba and Harcliffe (yes, Harcliffe) settle down to a married life of love and comfort after Harcliffe is rewarded for his wife’s heroism with what is apparently a well-remunerated government job.

This was not Bobby’s fault, and his story is a sad one. It’s not just recently that child labor in the land of Disney has been less about laughter and hopes than tears and fears.

To friends and loved ones who would suggest that I replace the “but” in this sentence with an “and,” I hear you.

My favorite example might be Egeaus, the narrator of “Berenice,” which is one of Poe’s stories about pale tubercular maidens. On one level, “Berenice” succeeds precisely as Poe means it to, and I mean this without irony. On another, it is the greatest comedic masterpiece written by someone who didn’t mean to be funny.

Oh this was a joy to read. I was a precocious reader and lover of words from the start, usually keeping my giant red dictionary companionably nearby for those moments when I'd need to look up a juicy new word (which I often wrote down and taped up on my bedroom wall). This brought back happy memories of those days.

Now I'm in the thick of teaching my own kids to read and hopefully to love reading. I'm reading aloud Rosemary Sutcliff's Black Ships Before Troy to them currently and Sutcliff wields good plain words marvelously: "Menelaus' queen was fairer even than the stories told, golden as a corn-stalk and sweet as wild honey." And this one gave me chills: "So Paris had the bride that Aphrodite had promised him, and from that came all the sorrows that followed."

I imagine that those curtailed dictionaries are remarkably unworn. Children who are likely to look up a word are unlikely to need such a dictionary because they already know the simple words in it, and children who are unlikely to look up a word are unlikely to *use* such a dictionary even if they need it. What crisp pages they must have! You were steering parents well.