Artful Humbug

Prose style in “A Christmas Carol.”

Charles Dickens partly reshaped Christmas through writing about it, and he succeeded in doing so for a number of familiar reasons. His images are memorable and briskly colored. His characters stick in the mind as singular people despite his economical characterization, and do so even for readers who find creations like Tiny Tim and Mr. Fezziwig more sentimental than they prefer. The novella’s themes are direct by the standards of modernism—and by the standards of whatever thing comes after that—but even now there remains an audience for generosity, affirmation, pity, joy, charity, and deference to the passage of time. “A Christmas Carol” is still with us because Dickens tells a vivid, human story that doesn’t deface the good or the true.

But there is also some inspired sentence-making in the book even though Dickens isn’t a paragon of style either for hair-shirted minimalists or for Flaubertians quivering in anticipation of le mot juste.1 The brilliance of Dickens as a stylist lies in his exuberance, his appreciation of tone color, his lack of inhibition, and his understanding that idiosyncratic constructions can achieve a kind of ramshackle grandeur. He writes sentences like someone who has read a lot of Shakespeare aloud but also listened attentively while walking down the street.

“A Christmas Carol” gets us off to a brilliant start:

Marley was dead: to begin with.

Benjamin Dreyer recently pondered whether the opening sentence contains the “best colon ever,” and he’s surely right to put it in the running. Better than a comma, and better even than a dash: the colon makes the pause as pregnant as a pause can be: which draws our attention to both the death aspect of the sentence and the “begin with” aspect: both of which resonate throughout the rest of what Dickens has in store for us.

A plain language enthusiast would call the colon eccentric and denounce the placement of the prepositional phrase as an unnatural inversion. A plain language militant would recommend omitting the prepositional phrase entirely on the grounds that opening sentences are inherently things that we “begin with”:

To begin with, Marley was dead. (←Write like a normal person!)

Marley was dead. (←Cut the deadwood!)

The problem with both of these solutions is that they rob us of the richness and thus the significance of “to begin with,” which means several things at once:

a. This is the beginning of this story. (Note, though, that it will begin again a few pages later, in the disenchanted counting house, with “Once upon a time.”)

b. Pay attention! Death is an important theme.

c. Marley has died here where we’ve begun, but we’ll also be hearing from him soon.

d. Marley, like Scrooge, was dead inside “to begin with,” even when he was alive.

e. Pay attention! As per point (b) above, death is an important theme for you, just as it was for Marley and is soon to be for Scrooge.

Some of these meanings are hidden from the first-time reader of “A Christmas Carol,” but great writers write for re-readers. The revealed genius of the colon and the syntax awaits our return.

Not long after the well-known description of Scrooge as “a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old sinner” comes this:

The cold within him froze his old features, nipped his pointed nose, shrivelled his cheek, stiffened his gait; made his eyes red, his thin lips blue; and spoke out shrewdly in his grating voice.

The cold performs six actions if you’re counting verbs, but it’s in fact seven since it makes different things happen to eyes and lips. The semicolons allow for the beautifully asymmetrical symmetry of “made” working with the other five verbs while simultaneously being singled out with two mid-series direct objects (“his eyes” and “his thin lips”), each with its own object complement (“red” and “blue”).

The final verb, “spoke out,” is the most fascinating because it’s the most unusual when traced back to its subject: “The cold . . . spoke out.” It also transforms Scrooge into a particularly pathetic kind of ventriloquist’s dummy. The cold itself—and not Scrooge the man, or at least not the man he ought to be—is the speaker.

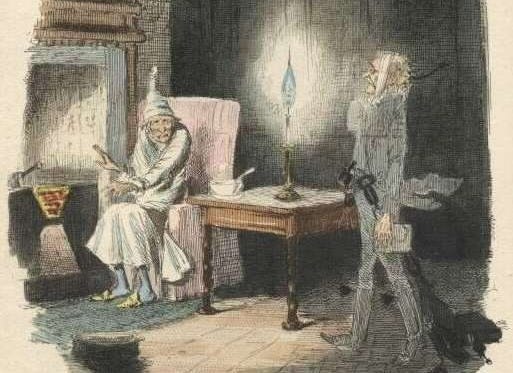

When Scrooge doubts the existence of Marley’s ghost, and Marley asks him why he won’t trust his very own senses, Scrooge replies,

“A slight disorder of the stomach makes them [Scrooge’s senses] cheats. You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of an underdone potato. There’s more of gravy than of grave about you, whatever you are!”

Dickens makes Scrooge eloquent in his cussed unbelief, even more eloquent than he is in his earlier callousness about workhouses and “the surplus population.” The parallel series of four hallucinogenic food particles flouts the rule of three and is individuated with “bit,” “blot,” “crumb,” and “fragment.”

I admit that the “gravy” pun may not be Hamlet-level work, but it’s in shouting distance of the dying Mercutio’s “tomorrow . . . you shall find me a grave man.” ’Twill serve.

After the Ghost of Christmas Past has led Scrooge to see himself as a boy, reading alone in an empty school, neglected by his friends, Ebenezer the old man has this reaction:

Not a latent echo in the house, not a squeak and scuffle from the mice behind the panelling, not a drip from the half-thawed water-spout in the dull yard behind, not a sigh among the leafless boughs of one despondent poplar, not the idle swinging of an empty store-house door, no, not a clicking in the fire, but fell upon the heart of Scrooge with a softening influence, and gave a freer passage to his tears.

At seventy-six words long, and with a wait of fifty-seven words to get to the predicate at “but fell,” and with the inclusion of details about mice scufflings and partly frozen backyard water-spouts and a depressed tree, it’s not a sentence to emulate if one wants to appeal to the impatient reader; but sometimes one wants to give one’s affections to those readers who are patient enough to let the details of the scene fill out, who are willing to take the time to feel bad for the tree and the boy, and who will hold fast to their anticipation long enough to let the tears fall exactly as freely and heavily as they should.

When the Ghost of Christmas Present shows Scrooge the shops on the street on Christmas Eve, Dickens allows his sentences to get weird:

There were great, round, pot-bellied baskets of chestnuts, shaped like the waistcoats of jolly old gentlemen, lolling at the doors, and tumbling out into the street in their apoplectic opulence. There were ruddy, brown-faced, broad-girthed Spanish Onions, shining in the fatness of their growth like Spanish Friars, and winking from their shelves in wanton slyness at the girls as they went by, and glanced demurely at the hung-up mistletoe.

Here we get the Dickens who was not immune to a well-turned ankle.2 The slyness of the second sentence, though, is in the delay of the surrealistic turn with the “like Spanish Friars” simile, and in the very demure girls’ unexpected reciprocity given that they’re in the Dreamland of the Anthropomorphized Onion Friars. The sentence is fabulistic enough to be in one of Gogol’s early stories about fairytale Ukrainian villages.

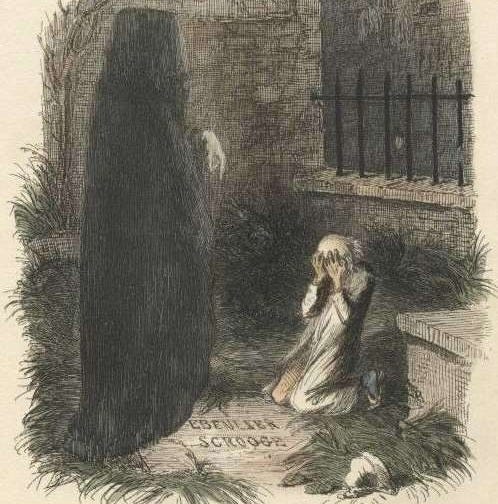

The next-to-last section, or fourth stave, featuring the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, begins on a chilly, sinister note, and also with a thematically appropriate pun, though this time with no hope of gravy:

The Phantom slowly, gravely, silently, approached. When it came near him, Scrooge bent down upon his knee; for in the very air through which this Spirit moved it seemed to scatter gloom and mystery.

It was shrouded in a deep black garment, which concealed its head, its face, its form, and left nothing of it visible save one outstretched hand. But for this it would have been difficult to detach its figure from the night, and separate it from the darkness by which it was surrounded.

Although Dickens enjoys his lists and coordinating conjunctions even in this mode, his phrasing is more compact, and words with Germanic and Norse roots are especially prominent: “slowly,” “gravely,” “bent,” “knee,” “scatter,” “gloom,” “shrouded,” “deep,” “black,” “head,” “hand,” “night,” and “darkness.” These words were very likely the product of Dickens’s ear rather than deliberate etymological choices, but what a remarkably perceptive organ his ear was.3

The only thing I would change about the passage would be to reverse the order of “gloom” and “mystery” at the end of the first paragraph:

. . . it seemed to scatter

gloom and mystery.. . . it seemed to scatter mystery and gloom.

The mystery should have led into the darkness rather than the other way around, and the iambic pattern would have come to rest more truly with the resounding final beat of “gloom.”

Dickens does something fascinating with Scrooge’s manner of speaking in the midst of his exultant transformation in the first part of the final section, or fifth stave. Twice he says, “Thank’ee,” most likely because he is so overcome with emotion that he reverts to a less refined manner of speaking from his childhood. (The one instance of “thank’ee” in Bleak House comes from Jo, the homeless street sweeper, who a moment later says, “I never know’d nothink about ’em.”) Scrooge says “thank’ee” once earlier to Marley’s Ghost, though the extreme emotion in that scene is terror rather than joy.

Scrooge also reverts to the language of his child self when he refers to the servant girl who answers his nephew’s door as “my love.” Tolkien has something similar happen to Samwise Gamgee at the end of The Two Towers when Sam thinks his master is dead and refers to him as “me dear, me dear.”4

The craft decision to use “thank’ee” and “my love” is derived from Dickens’s social and emotional insight, but it also makes a thematic contribution by suggesting that the change in Scrooge is not about becoming someone entirely new. His moral redemption is less a transformation into something new than it is a reversion, a way of sloughing off the dead tissue that has so disfigured his older self, a remembering of the person he ought to be.

The end of “A Christmas Carol” is easy to dismiss as sentimental, and I admit that I’m not nodding along vigorously when Dickens moves toward his conclusion with cheery talk about “the good old city” of London in “the good old world.” Even though I’m won over by Nabokov’s rendering of existence as a gift in his final Russian novel, and won over by Auden’s pledge to show an affirming flame, these things don’t always come easily to me.

My fallen nature does, however, allow me to appreciate the mischief with which Dickens opens the final paragraph of “A Christmas Carol”:

[Scrooge] had no further intercourse with Spirits, but lived upon the Total Abstinence Principle, ever afterwards.

Though I offer this up for personal study rather than to ruin it with exegesis, I will say that it’s a noteworthy example of the bounty of Dickens which allows him to overcome what would be hard to tolerate in lesser writers.5 Tiny Tim’s request for a blessing for everyone at the end of the paragraph becomes both more radical and less moony-eyed because Dickens encompasses so many moods, attitudes, ways of being, and stylistic variations. It’s enough to make my heart grow a size or three.

I’m with the Flaubert faction if I have to choose between them and the hair shirts. Loving good writing, though, and even the very best writing, isn’t compatible with insisting on a stylistic One True Faith.

I’m well aware there was more than good Christmas fun in this. Complaints are of course welcome.

If sound and meaning are more than casual acquaintances, then reading Dickens is a fine way to resist Saussurean declarations about the arbitrary relationship between signifier and signified. Kiki and Bouba are two different people, and “A Christmas Carol” with a hero-villain named Sebastian Cavendish is not the same story as “A Christmas Carol” with a hero-villain named Ebenezer Scrooge.

Bad readers are prone to reading both of these moments badly—sometimes with an insufferably knowing wink.

People attribute a similar quality to Walt Whitman, but it doesn’t work for me as well with Whitman because he keeps getting himself confused with the cosmos.

This is a great close reading. I love that you corrected the order of “gloom and mystery.” Everyone needs an editor!